There was something about the word Duplex that really seemed to get them going, down in the OEC works on the South Coast of England. It was duplex with everything when it came to advertising their products – maybe twice as safe, twice as steady and, perhaps, twice as desirable was the aim; who can be certain now, why they latched on to this terminology, but it was to serve them well from the mid 20s through to World War II. 'The Osborn Engineering Company Ltd,' of Atlanta Works, Highbury St, Old Portsmouth rather specialised in slogans anyway, Built Like a Battleship was one of their regulars, as was The Modern Motor Cycle and, like many a smaller maker, they had to try hard to be different from the big boys, to impress their products in the minds of the buying public.

Where they differed from most was in the bold manner with which they always embraced the unconventional; not for OEC the stodgy road of strengthened bicycle frames and forks, nor always conventional engines, every time they were 'way out man'. From the Blackburne steering wheel sidecar taxi outfit of 1921, to the enclosed Whitwood Mono-car and 'feet forward' Atlanta Duo of the mid 30s, this company held the candle for oddities. Not that their mainstream products were all that normal, but they were more recognisably motor bicycles and sold in sufficient numbers to keep them in business until the Hitler war.

Where they differed from most was in the bold manner with which they always embraced the unconventional; not for OEC the stodgy road of strengthened bicycle frames and forks, nor always conventional engines, every time they were 'way out man'. From the Blackburne steering wheel sidecar taxi outfit of 1921, to the enclosed Whitwood Mono-car and 'feet forward' Atlanta Duo of the mid 30s, this company held the candle for oddities. Not that their mainstream products were all that normal, but they were more recognisably motor bicycles and sold in sufficient numbers to keep them in business until the Hitler war.

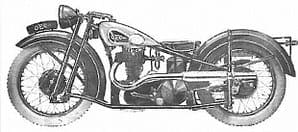

Their Duplex frame first appeared in late 1924, with duplicated saddle tubes, chain stays and engine cradle tubes; it was unsprung and carried girder forks at the front. Not for long though, as by '27 the world was deemed ready for and OEC speciality, in the shape of Duplex steering. Easier to view in action than to describe on paper, this system involved the engine cradle tubes being brought forward almost to the centreline of the front wheel and bowed outwards for turning clearance. The wheel was steered via near vertical spindles and links turning on taper roller bearings, with the forward spindles on each side carrying the wheel in tubes slotted for suspension movement, controlled by coil springs. There was a strong self centring effect to the steering, made great play of by OEC who claimed it as a safety feature. The effect was so strong that even a heavy blow on the handlebar wouldn't send the bike off course.

The Duplex Steering was quickly followed by rear springing for the frame, again, an unusual arrangement appeared, in which a pivoted fork was controlled by plunger spring units added to the rear fork ends. Links joined the fork to the units, which were in turn bridged over the back mudguard. Not altogether pleasing to the eye, the OEC design did however allow for easy carrying of a pillion passenger, provided for almost constant tension of the drive chain and ensured that the wheel was very well supported indeed.

The general design was used by several continental manufacturers, but wasn't widely seen in Britain; perhaps best remembered today would be Royal Enfield's similar effort on the Ensign lightweight of the 1950s. Inside these cycle parts was to be fitted a host of motors including Villiers, JAP, Sturmey-Archer, Blackburne, OEC-Temple, Vulpine and even the V4 Matchless Silver Hawk.

The general design was used by several continental manufacturers, but wasn't widely seen in Britain; perhaps best remembered today would be Royal Enfield's similar effort on the Ensign lightweight of the 1950s. Inside these cycle parts was to be fitted a host of motors including Villiers, JAP, Sturmey-Archer, Blackburne, OEC-Temple, Vulpine and even the V4 Matchless Silver Hawk.

You specified it and Atlanta Works would fit it; if it would go in. The rear springing became a standard fitment, but the Duplex Steering was always to be an option, girders remaining a cheaper alternative and referred to by OEC as their Fork Steering models. By 1935 power units from H. Collier & Sons (who were Matchless and AJS of course) had established themselves as the standard OEC wear, although the company ignored the Matchless origins and catalogued them all (from 250 to 1000cc) as having OEC engines; helped by the willingness of Collier's to cast any small makers' own namestyle into the magneto drivecase.

The range then continued with little radical change (except that the engines were changed to AJS type, with front mounting magnetos in 1937 and the rear springing revised) for four years, during which time Osborn were busily engaged in banging their heads hard with that F.F. Atlanta Duo and the even more unlikely Whitwood Monocar.

Extricating themselves from the inevitable blind alleys that both had lead to, they turned their attention again to the almost conventional roadsters in 1939 and came up with Duplex Girling Braking on the new, range topping, Commodore model.

Two 7" diameter Girling pattern wedge action brakes were fitted into both wheels of the Commodore giving twice the stopping area of the lesser models; each being located within neat light alloy muffs. Duplex Steering was still an option and rear springing standard through the range.

Cleaner and tidier in appearance than before, the earlier pivoted fork had been replaced by short individual arms, each under the control of a friction damper; not unlike Ariels link-springing in appearance. Finished in grey enamel, with chromium plated tank and wheel rims, outlined in blue and lined in gold, the 500cc Commodore was to be the high point of OEC fortunes. Duplex Cradle Frames, Duplex Steering and Duplex Braking were there at the end, a good looking package, for anyone requiring something a little different, but not too outrageous.

Cleaner and tidier in appearance than before, the earlier pivoted fork had been replaced by short individual arms, each under the control of a friction damper; not unlike Ariels link-springing in appearance. Finished in grey enamel, with chromium plated tank and wheel rims, outlined in blue and lined in gold, the 500cc Commodore was to be the high point of OEC fortunes. Duplex Cradle Frames, Duplex Steering and Duplex Braking were there at the end, a good looking package, for anyone requiring something a little different, but not too outrageous.

As the war years drew to a close, OEC ran a tempting advert, suggesting that the Commodore would be on sale again once hostilities ceased, but it never was; in fact the company didn't get into motorcycle manufacture again until 1949 and then with a Villiers engined lightweight of no particular distinction. They soldiered on for half a dozen years, coming up with a novel swinging arm design featuring a countershaft running through its pivot point to give a constant rear chain tension.

However, the complication of the two chains that were required (from the gearbox to the countershaft and then to the rear sprocket) plus the added weight, offset any theoretical advantage. It was so typical of OEC ingenuity, but this time the public didn't buy and they faded soon after. The Duplex touch had deserted them at last. ![]()

See also When was it that? contents