It was on the 1st April 1947 that Bert Hopwood joined Norton Motors Ltd, in the capacity of Chief Designer. His immediate priority was to design a vertical twin that would help revitalise the company's range of products. All they had to offer at the time of his appointment were six elderly models; two side valve singles, two overhead valve singles and, two overhead camshaft models made in limited numbers – plus, of course, the racing singles for which they became world famous. The road going models were pre-war designs, to which Norton's own 'long' Roadholder telescopic front fork had been added from 1947 on. To use Hopwood's own words, "All of the motorcycles we then produced were unbelievably noisy" and, he recalls one of Norton's largest dealers pleading with Gilbert Smith, the Managing Director, not to consider making a twin as he feared the engine noise would be doubled!

Hopwood was clearly the man for the job, as he had joined Ariel as a junior draughtsman at the age of 18, after having won a college memorial prize for design engineering. His first boss was the legendary Val Page, but later he became assistant to Edward Turner soon after the latter had joined the company as a forward design engineer. He had worked closely with Turner on the design and development of the latter's Square Four and later still, on the Speed Twin that followed, after Ariel's boss, Jack Sangster, had acquired Triumph and transferred Turner to Coventry. Turner invited Hopwood to join him and he remained with Turner until their relationship deteriorated and it was time to seek fresh fields.

In designing his own vertical twin engine, Hopwood's problems were twofold. Not only did he need to overcome some of the shortcomings of the Triumph engine, which he knew only too well, but he also had to avoid the risk of patent infringement. Cylinder head overheating had been one of Triumph's main problems, partially offset by using light alloy materials. Norton's financial constraints did not permit him to follow this route, so instead he arranged the Norton valve gear in a splayed out configuration, so that there would be a free passage of cooling air between the inlet and exhaust ports. Furthermore, as much of the mechanical noise in a Triumph engine comes from the timing chest, he settled for the use of only a single camshaft at the front of the engine, with the valve gear driven by short, endless chains. He would have preferred to use a one-piece crankshaft too, but the somewhat primitive machining facilities at Bracebridge Street would not have permitted this. Instead, he had to revert to a built-up, three-piece crankshaft like Triumph, incorporating some subtle design changes that avoided confliction with Triumph's own patents.

'Upright' gearbox

The traditional Norton 'upright' gearbox received attention too, in the form of what Hopwood described as a "facelift". Its internals were essentially as before, but they were housed in an entirely new horizontal shell.

This meant that the long, slender gear-lever, which required excessive movement, could be replaced by a much shorter lever, to ensure a more positive change. It was less likely to be affected by wear in its operating joints too. This new design was subsequently fitted, with advantage, to the other touring models.

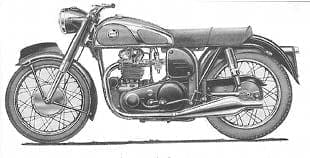

A new frame was designed, similar to that of the ES2, and having plunger-type rear suspension. A 'long' Roadholder fork was fitted at the front end and both mudguards were of generous proportions; the rear one having a stylish flare at its rearmost end. The petrol tank was pleasantly styled too, slimmed down in the vicinity of the kneegrips. It embodied a characteristic fold line in the centre of its top surface, with an oil pressure gauge sunk into the top on the lefthand side. The overall finish of the machine was in black, relieved by the chrome-plated petrol tank with its silver panels surrounded by a thin red and a wide black outline.

Designated the Model 7, the twin made its first appearance at the 1948 Earls Court Show where, as a last minute surprise, it created quite an impression.

Designated the Model 7, the twin made its first appearance at the 1948 Earls Court Show where, as a last minute surprise, it created quite an impression.

Priced at £170, this included £45.18.0 Purchase Tax, but not the £4.0.0 needed for a speedometer – an absurd optiional addition generally made by manufacturers at that time, as a speedometer was an obligatory fitment!

Bore and stroke dimensions were 72.6mm x 66mm, giving a capacity of 497cc. Wheel sizes were 21" front and 19" rear, and the overall weight 4381bs. The catalogue issued at this time optimistically stated that a light alloy cylinder head and barrel could be obtained at extra cost, but these options failed to materialise.

With a high level of interest and many orders, it may seem surprising that it took so long for the Model 7 to get into production. Unfortunately, it was seriously delayed by some behind-the-scenes politics, when Joe Craig seemed to place every possible obstacle in its way.

He had fallen out with Hopwood after the latter had submitted a 10-year plan for future development, which included an ohc version of the twin and even a 4-cylinder racer.

Beloved single

Anything that would conflict with his beloved single cylinder Manx racers was seen as a personal affront and, from that point on, he and Hopwood failed to see eye to eye. Although the new twin had passed all its tests with flying colours, Craig used every delaying tactic possible.

By the time he had run out of excuses, Hopwood had been dismissed "on the score of economy", as the board put it. His twin finally went into production, virtually unchanged, but without its designer present to take the credit.

The Model 7 became known as the Dominator in 1949, and by 1951 it had become available with the option of the famous 'featherbed' frame. The engine itself had an exceptionally long life.

The Model 7 became known as the Dominator in 1949, and by 1951 it had become available with the option of the famous 'featherbed' frame. The engine itself had an exceptionally long life.

It was successively stretched in capacity to 600cc, then 650cc and finally 750cc, with the launch of the mighty Atlas. Later still, it formed the motive power for the Commando, initially in 750cc form, but later stretched still further to 850; being isolated from its chassis by the ingenious Isolastic suspension system that ensured the rider did not suffer from the effects of excessive vibration.

With a lifespan of almost three decades, Hopwood's engine proved a worthy alternative to Edward Turner's original concept, and did much to keep the Norton name alive. ![]()

See also Now when was it that? contents