Like many of Britain's former motorcycle manufacturers Ariel were in at the very beginning. Although it was not until 1902 that they made their first motorcycle, their association with transportation of one kind or another goes back much further.

The first known use of the name Ariel had occurred in connection with a horse-drawn carriage wheel, although no one knows for sure what prompted its use. It was not until 1871 that the name was identified with a complete road vehicle – in this case the humble bicycle. Unconnected with the earlier venture, it was adopted by James Starley as the trade name for a bicycle of his own design and manufacture. So, although the early origins of Ariel can be traced back to the City of Coventry, the company did not remain there for long. By the time the manufacture of motorcycles had begun, the company (by now known as Cycle Components Manufacturing) had been transferred to premises in Selly Oak, Birmingham, where they were to remain until the production of motorcycles there ended and was transferred to Small Heath.

That Ariel Motors made a substantial contribution to the British motorcycle industry there can be no doubt. Designs such as the Square Four and the Red Hunter range of singles set hitherto unknown standards, and after World War 2 came the Ariel twins (which many considered preferable to the BSA twins they so closely resembled) and later still, the Leader and Arrow two-stroke twins. Had it not been for their trials and scrambles models, the competition world would have been all the poorer too.

There was a remarkable amount of talent within the company, all under the shrewd guidance of Jack Sangster who had rescued it from bankruptcy in late 1932. In those early days he was indeed fortunate to have working for him three very capable designers, all of whom left their mark in motorcycle design – Val Page, Edward Turner and Bert Hopwood.

In late 1935 Ariel were acquired by BSA, a move which, in later years, Jack Sangster had cause to regret. For a considerable while they continued to retain their autonomy, although the manufacture of Ariel four-strokes finally came to an end during August 1959. Thereafter production concentrated on a 249cc two-stroke twin that was to replace them. First came the fully enclosed Leader and then two further unenclosed variants, of the same model, the Arrow and the Arrow sports models. These were the last designs to originate from Val Page and indeed from Ariel's Selly Oak premises, as it was during the spring of 1963 that the factory was closed and all production transferred to BSAs premises at Small Heath. There they had to suffer the introduction of yet another new model, what amounted to a 50cc version of BSAs 75cc ohv Beagle.

In late 1935 Ariel were acquired by BSA, a move which, in later years, Jack Sangster had cause to regret. For a considerable while they continued to retain their autonomy, although the manufacture of Ariel four-strokes finally came to an end during August 1959. Thereafter production concentrated on a 249cc two-stroke twin that was to replace them. First came the fully enclosed Leader and then two further unenclosed variants, of the same model, the Arrow and the Arrow sports models. These were the last designs to originate from Val Page and indeed from Ariel's Selly Oak premises, as it was during the spring of 1963 that the factory was closed and all production transferred to BSAs premises at Small Heath. There they had to suffer the introduction of yet another new model, what amounted to a 50cc version of BSAs 75cc ohv Beagle.

Ariel Pixie

This was the Ariel Pixie, of which probably the least said, the better. It was only a short stay of execution, however. By the autumn of 1985 production finally ground to a halt and to all intents and purposes it marked the end of Ariel Motors. Sales had tailed off to the extent that BSA no longer regarded the company as a viable asset. Yet although no one may have realised at the time, one final indignity had still to come. The ghost of Ariel was about to manifest itself in such a way that it would only heap scorn on this once hallowed name.

George Wallis was no newcomer to motorcycling when he approached the BSA board with what appeared to be a novel design for a three wheel moped. In the early days of speedway racing (or dirt track racing as it was called then) he had designed a new type of frame that was specially suited to this type of racing. Wal Phillips was the first to use it in conjunction with the prototype JAP engine, and it performed so well that it made Wal a star rider virtually overnight. It also led to an agreement with Comerfords of Thames Ditton to manufacture the Comerford Wallis speedway bike under licence.

He had been out of the motorcycle business for some while, repeating his run of successes in other ventures. It was only by chance that he became involved again whilst he was on his way to a holiday in Portugal. On his way there he came across quite a few mopeds carrying heavy loads for which they were obviously ill equipped. This led him to give thought to some similar type of machine that would carry a moderate load with complete safety, possibly a three wheeler that could be made to handle like a bicycle. He became so obsessed with this idea that by the time he arrived at his destination he had already sketched out a rough design, which he then turned into a complete set of drawings before he returned home.

He had been out of the motorcycle business for some while, repeating his run of successes in other ventures. It was only by chance that he became involved again whilst he was on his way to a holiday in Portugal. On his way there he came across quite a few mopeds carrying heavy loads for which they were obviously ill equipped. This led him to give thought to some similar type of machine that would carry a moderate load with complete safety, possibly a three wheeler that could be made to handle like a bicycle. He became so obsessed with this idea that by the time he arrived at his destination he had already sketched out a rough design, which he then turned into a complete set of drawings before he returned home.

Umberslade Hall

His first approach was to the BSA staff at the infamous Umberslade Hall, which much to his surprise met with a rebuff. They were not in the least impressed. However, Lionel Jofeh, BSA's Managing Director at that time, disagreed with their decision. Over-reacting wildly, he saw this design as one that would revolutionise public transport, attracting custom away from the underground and buses.

Setting aside Umberslade's rebuff, he passed the idea over to colleagues of his who had also joined BSA from the aircraft industry and had no previous experience of motorcycles. That proved to be the first in a series of fatal moves that would prejudice the project right from the very beginning. It took a full 12 months of negotiation for George Wallis to arrive at a final agreement with BSA, and it was fortunate that he managed to have an escape clause included in it. In effect this permitted his design to revert back to him if certain of the agreement's conditions were unfulfilled.

What emerged from BSA bore little relation to the original Wallis design, with the result that George regained his sole rights and was able to persuade Daihatsu, the Japanese car manufacturer, to take up his design after only two weeks discussion. As a result it went into limited production in Japan, virtually unchanged. Unfortunately an unfavourable price differential of almost three times that of the British version ensured it was never imported into the UK. Later still, Honda subsequently acquired the rights, which it is alleged resulted in the production of their Stream scooter, even though that too was very expensive and short lived.

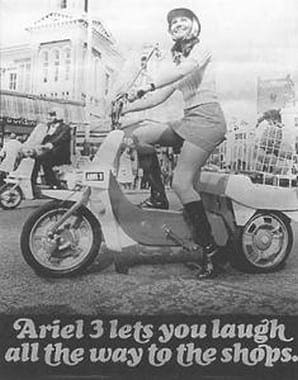

BSA's deviant of the Wallis design was marketed as the Ariel 3 in May 1970, although why the Ariel name was revived for this disastrous marketing exercise is far from clear. Even BSA seemed uncertain about exactly what they were trying to sell, one of their advertisements being headed 'Here it is. Whatever it is.'

About the only innovation retained from the original Wallace design was that the front half of the machine banked over steeply when cornering, as was originally intended. No longer was the engine mounted well forward of the twin rear wheels, a modification which not only made it less stable but also reduced its rear luggage-carrying capacity at the same time. The BSA version was based on the Dutch made 48cc Anker engine, a single cylinder fan-cooled two-stroke, which drove a countershaft by a toothed belt via a centrifugal clutch.

About the only innovation retained from the original Wallace design was that the front half of the machine banked over steeply when cornering, as was originally intended. No longer was the engine mounted well forward of the twin rear wheels, a modification which not only made it less stable but also reduced its rear luggage-carrying capacity at the same time. The BSA version was based on the Dutch made 48cc Anker engine, a single cylinder fan-cooled two-stroke, which drove a countershaft by a toothed belt via a centrifugal clutch.

Starting was accomplished by using the pedals which engaged with the engine via a sprag clutch. What often proved to be an essential feature was the incorporation of a simple dog clutch so that the tricycle could be pedalled home when the engine failed. Suspension was provided by two torsion bars that also returned the front half upright after it had been banked over whilst cornering. They could be adjusted, to take into account the rider's weight. The rear axles were live (the right-hand one a dummy) and of the two rear wheels, only the left hand one was driven and braked. All three wheels were interchangeable, car fashion. Weather protection was provided by built in leg shields and there was a windscreen attached to the handlebars. Luggage could be carried in an unlockable wire basket mounted above the 'bonnet' covering the rear mounted engine.

Ambitious target

Jofeh had set an ambitious target of producing 2000 a week, based on market research estimates that predicted a world wide market, and a correspondingly large number of Anker engines were purchased to be held in stock. Sadly, there was a vast difference between his expectations, its maximum speed being barely 30mph and its fuel consumption hovering around the 120mpg mark – hardy what one would expect from a moped. A whole list of other faults included difficult starting, poor engine reliability, a noticeable lack of power on hills, and peculiar handling problems. Furthermore, no means were provided for dipping the headlamp, there was no parking lamp, and only a feeble sounding horn. In the end only a few hundred of these machines were sold and within a very short period of time Pride and Clarke were selling off new Anker engines at ridiculously low prices. Exactly how much BSA lost as a result of this unparalleled marketing disaster is not known, although it has been estimated that if the tooling costs were taken into account and those of the lavish launch and the extensive market research exercise that preceded it, it is unlikely to have been less than £2,000,000. It contributed substantially to the demise of BSA at the end of 1972.

Anyone who has visited a classic motorcycle show at which the Exeter Classic Motorcycle Club has exhibited cannot fail to have been amused by the Ariel 3 that has appeared on their stand. Against the background of a western saloon it can be seen hanging from a noose on the gallows. A notice proclaimed it had been hung at high noon for impersonating a motorcycle! Whilst that just about says it all, one cannot help but feel sad that the once proud Ariel name should have been associated with this quite ridiculous design.

Could it have been quite different if George Wallis' original design had been adopted more or less as it stood, or was it that a market for this type of machine never really existed at all? The latter seems the more likely, but whatever the answer there can be little doubt that today even a virtually unused Ariel 3 will struggle to attract more than a £50 bid at an auction! ![]()

See also When was it that? contents