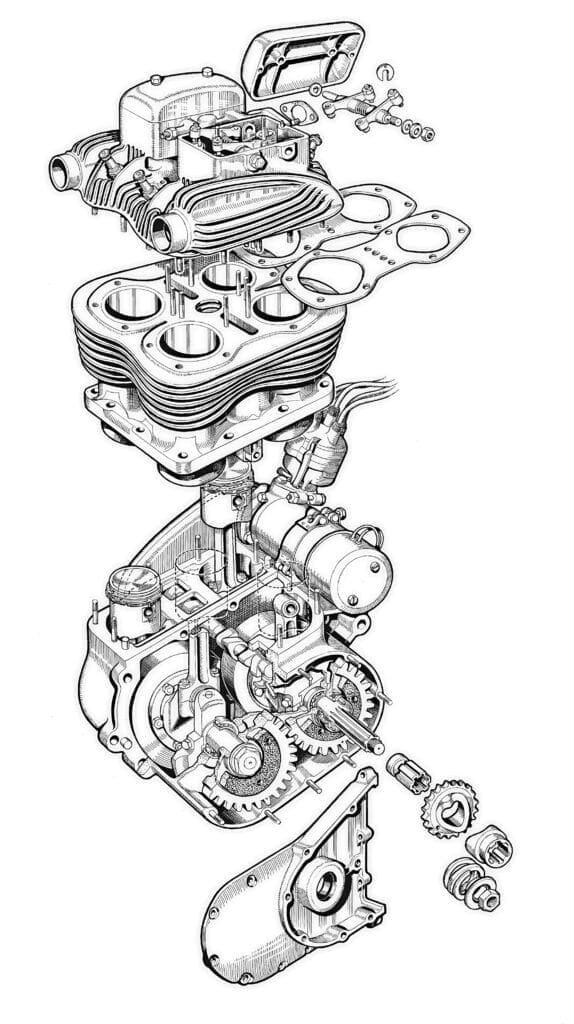

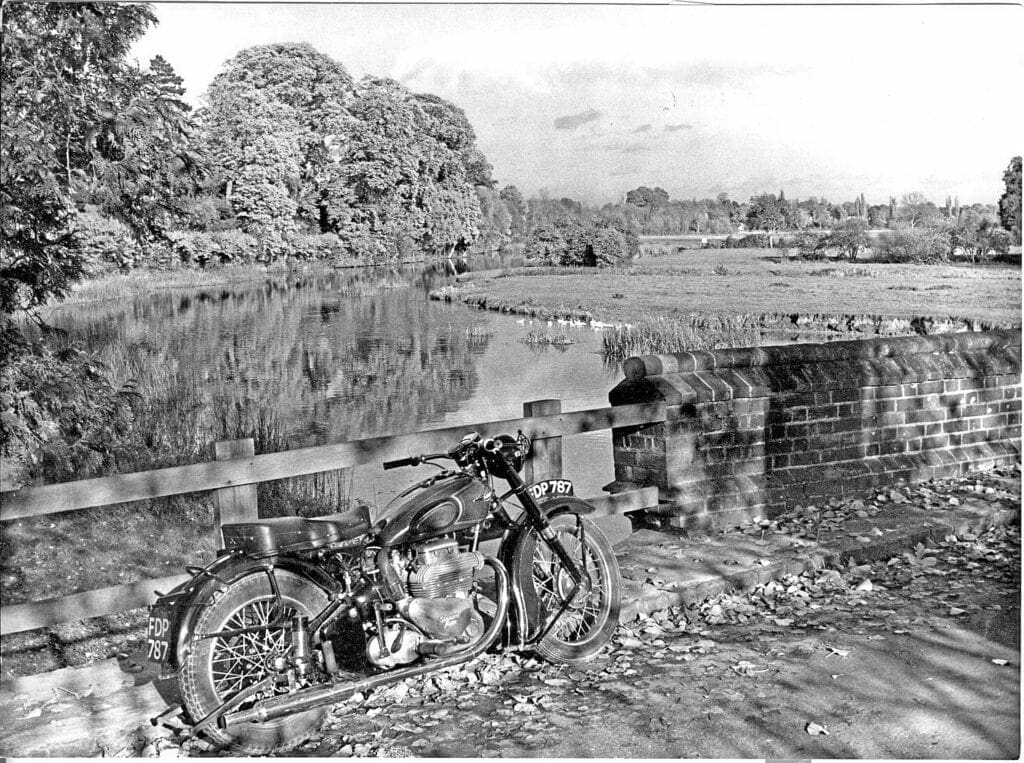

The uncanny flexibility of the Ariel Square Fours, from the 497cc and 597cc ‘cammies’ to the final pushrod-operated 997cc Mk. 2, always amazed those fortunate enough to road test these four-pot classics, as these excerpts from our archive bound volumes show.

All images: Mortons Archive www.mortonsarchive.com

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly newspaper.

Click here to subscribe & save.

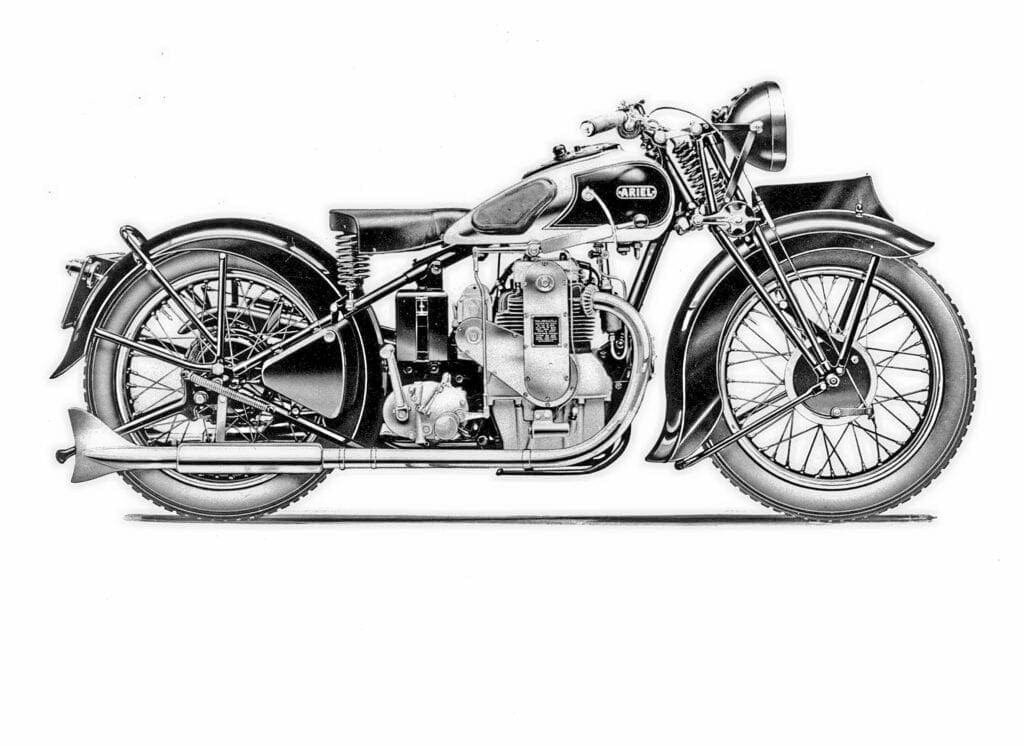

Last month, starting with the first published road test of the original 4F 497cc overhead-camshaft Ariel Square Four in The Motor Cycle of April 9, 1931, we gave a brief outline of the development of this fabled machine.

The euphoria that greeted the complex newcomer was mirrored in the report, with sentences like: “Becoming critical through experience, it is not often that the staff of The Motor Cycle can apply superlatives to almost every feature of a particular motor cycle.”

Within a year a 597cc model had been introduced, presumably for sidecar use, and for a while was sold alongside the original. By then the road testers, while still enthusiastic about the machine, had started to note a few faults as well.

Take The Motor Cycle’s January 7, 1932 road test of the larger-capacity machine, for example.

“Now that the Ariel Four has become almost a commonplace, it is much easier to be critical,” wrote the tester. “But happily, the 1932 model – made in 497cc and 597cc sizes – has gone still farther along the road towards perfection, and the few faults found in the 1931 model have been almost entirely eradicated.

“A great many machines have been in the hands of ruthless owners, and minor troubles, which even strenuous works testing failed to discover, have received attention.

“As a typical instance, there was a very definite tendency for the engine unit to cover itself in oil. It does so no longer. Again, the liability of the older model to ‘buck’ when at speed over bad surfaces has been removed by various means.

“In the case of the 597cc machine tested, this last improvement was most pronounced. With correct tyre pressures, the model at times seemed as though it were fitted with a spring frame, yet the only noticeable difference from the 1931 model was that the fork spring was considerably lighter.

“On fast bends, the Ariel kept its course accurately, and a touch of the rider’s knee would hold it down when travelling ‘hands-off’. No use was ever found for the damper in the course of 700 miles, and the rider, on one occasion, had the machine on full bore while working a stopwatch with his left hand, yet did not experience the slightest qualm.”

Those testers of old certainly got up to some hair-raising tricks!

“On comparatively freak surfaces the handling was very good for a machine equipped with standard tyres, and with a gentle throttle hand little or no wheel spin was experienced, save when the rear wheel was bounced by a rock.

“During an experiment the machine was held comfortably from 40mph with a locked and skating rear wheel. There was a tendency for the rear wheel to ‘judder’ when braking at high speeds.”

Although, whenever the air-cooled Ariel Square Four is discussed even today, many people ask about the rear two cylinders overheating, the 1932 road tester wrote: “As might be expected, the 600cc engine stands up to prolonged flogging without overheating, and has greatly improved low-speed characteristics.

“With the ignition retarded, it would tick-tock along in 7mph in top gear (though more evenly if a touch of brake was used to keep the load on the shock absorber constant) and at a touch of throttle would leap away smoothly and very quickly to speeds in excess of 70mph.”

By far the most interesting figures obtained in the test were those for acceleration. “From 10 to 30mph against the stop-watch, the figures were better than those obtained for any car tested by our sister journal The Autocar this year,” went the report.

“The very best of these were obtained for an 8000cc super-sports saloon – 42⁄5 seconds on any gear, and 7 seconds on top, from 10 to 30mph.

“This car was listed at £1850 and covered the flying quarter-mile at 101mph. For the 600cc, £70 machine the times were: top gear, 63⁄5 seconds; third gear, 53⁄5 seconds; and second gear, 41⁄5 seconds. In each case two attempts were made and the times checked.”

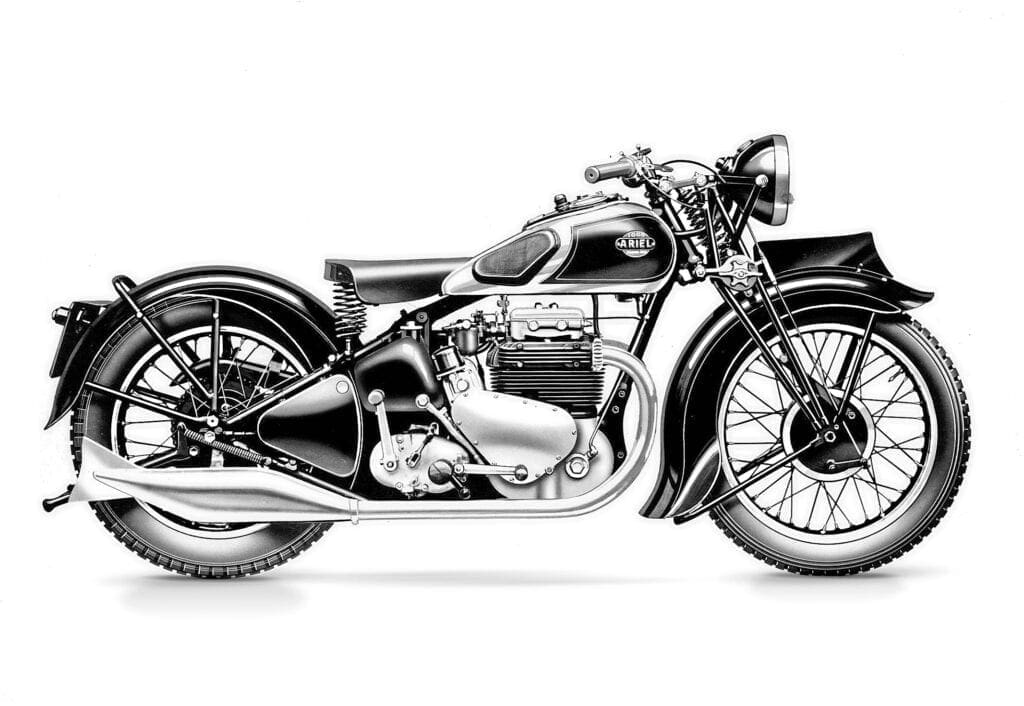

The tester’s comments about the 597cc engine standing up to prolonged flogging without overheating seem at odds with the general reputation the ‘cammy’ engine seems to have gained for exactly the opposite – and in 1936 the engine was completely redesigned as the 995cc overhead-valve 4G.

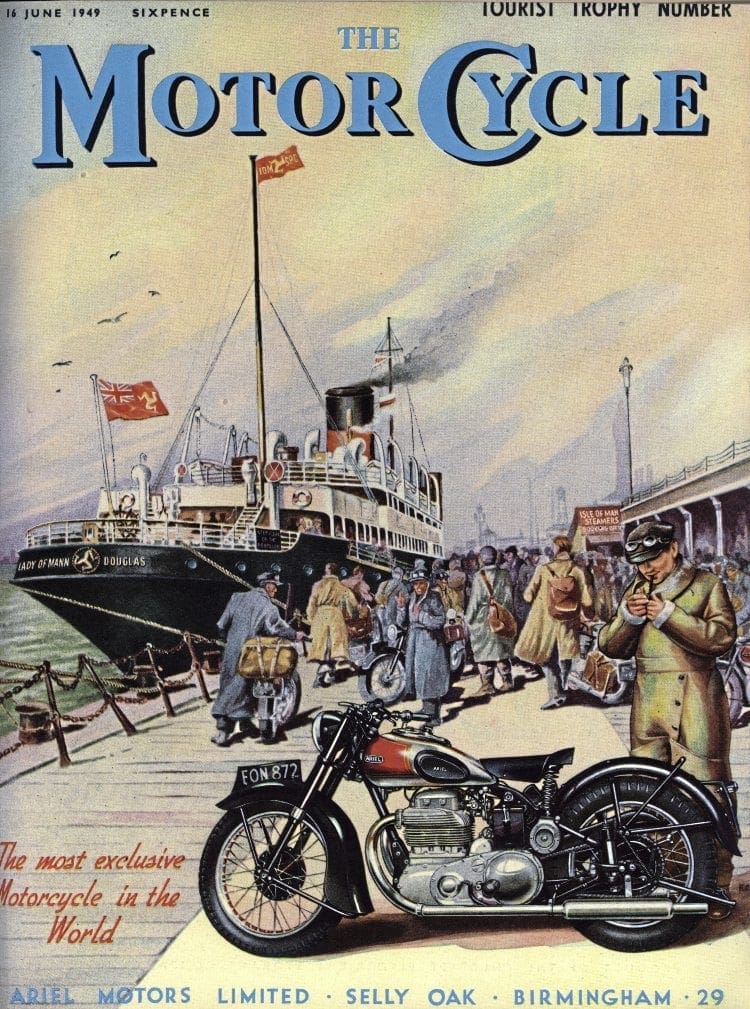

This takes us on to the next road test, of the Mk. 1 Squariel, which appeared in the May 26, 1949 issue of The Motor Cycle, and in which the legendary Cyril Quantrill played a part.

“The occasions on which a rider can look at his watch at the end of a run and say: ‘I just don’t believe it’ are very few indeed. Nevertheless a new ‘alloy’ 1000cc Ariel Square Four has several times during a recent road test been responsible for this incredulous murmur,” was the imaginative introduction.

“Lighter by no fewer than 32lb than its predecessor (the 1936 995cc 4G), with its cast-iron cylinder head and perhaps just a little more of a ‘good looker’, the new ‘Squariel’ combines the docility of a side-valve with an out-and-out performance that can be equalled by very few vehicles, whether two- or four-wheeled.

“Comfort is in keeping with performance: few forks can have as long a travel, and these, combined with a 4 x 18in rear tyre and the supple, unique design of rear springing make it necessary to search the car advertisements in American magazines in order to find words to do justice to the ‘ride’.

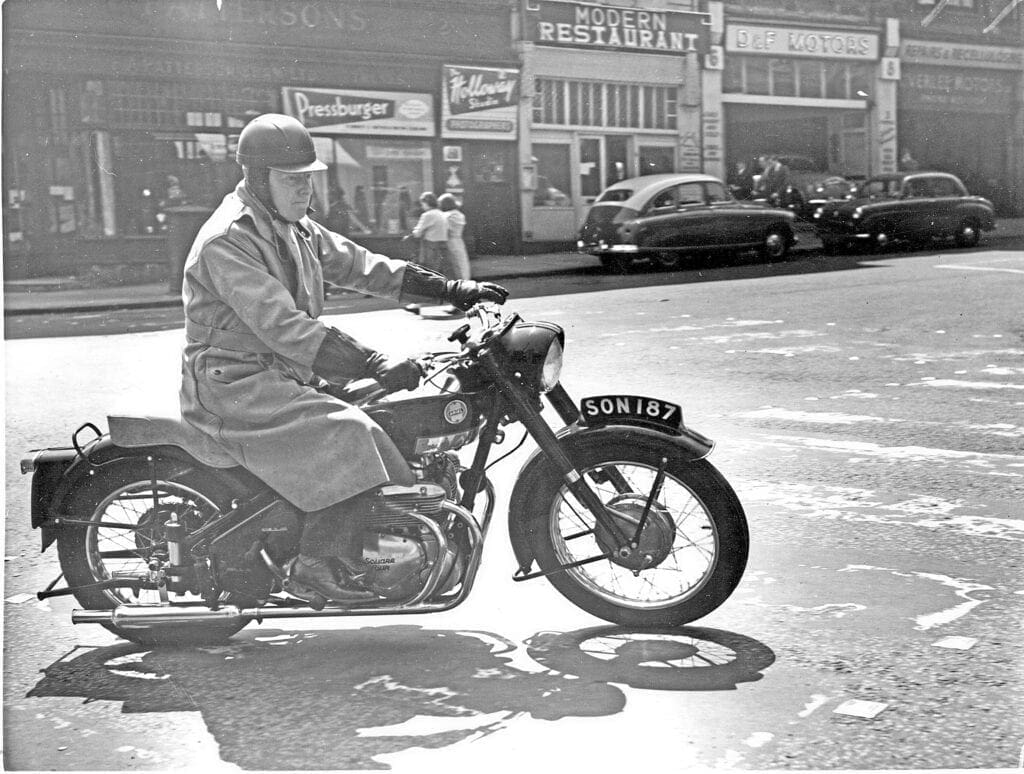

“In the hands of Cyril Quantrill, a large number of very fast miles were covered in the Continent before the actual test was started, and the machine’s first ‘official’ test run was from Birmingham to London. This is a trip made quite frequently and almost automatically, and normally the roads and towns pass almost unnoticed.

“Shock number one was received on arrival at Dunstable. A quick glance at the clock in the town square, followed by some simple mental arithmetic, produced an answer that would have enabled an ‘average speed’ discussion to keep going indefinitely in correspondence columns.

Shock number two followed a similar mental calculation at the end of the journey.

“All this was entirely without effort and with no fuss or bother. A large saddle with a raised back discourages the employment of any unnecessary ‘racer’ tactics, and the journey was done sitting upright and the only inconvenience suffered was from the large number of insects collected.

“Throughout this and similar journeys, there was little need to use the excellent Burman gearbox.

Occasionally, slowing down behind lorries on steep gradients, third gear assisted in initial overtaking but top was quickly selected again. It is possible, though of course a practice not to be recommended, to pull away in top gear from a standstill.

Minimum non-snatch speed in this gear is just over 10mph, and one could accelerate away without protest from the engine other than the ‘feel’ of each cylinder firing, while third-gear speed could be reduced to that of a fast walking pace.”

At the other end of the scale, performance was just as impressive, with acceleration from 20 to 80mph described as breathtaking.

Braking wasn’t quite up to scratch, though, with the tester observing: “The heavy total weight of 434lb must be responsible for the somewhat long braking distances recorded.”

Later in the test, despite the 32lb weight shaving of this new model, he also wrote: “When pulling the Ariel from the prop stand the weight was very apparent, and a stand that keeps the machine in a more vertical position would help.”

Engine noise wasn’t entirely absent, either. “Although at normal speeds the valve gear was difficult to hear above the wind and the swish of tyres, the sound of its operation was present as a continual subdued chatter,” he wrote. “Vibration was mainly confined to a period in top gear between 45 and 50mph, and could be felt on the overrun down through the engine rev range.”

The final Ariel Square Four design, the ‘four-pipe’ Mk. 2 that was built from 1953 until the end of production in 1958, was tested in the issue of Motor Cycling dated July 12, 1956.

With a redesigned cylinder head and four exhaust pipes to improve cooling, this machine retained the plunger rear suspension that dated back to 1939 (a prototype swinging-arm model never went into production) and produced 42bhp at 5800rpm.

After once again singing the praises of the engine’s flexibility, the Motor Cycling road tester was highly impressed by the Squariel’s stopping power. “The magnificence of both the Ariel’s brakes cannot be exaggerated,” he wrote. “The functional-looking full-width alloy front brake was fade-free, delicate in operation and completely trustworthy under hard application and in all circumstances.

“During the initial stages of the road test, a couple of ‘clicks’ on the patent fulcrum brake-shoe adjuster were needed to cater for the bedding-down of the linings,” he continued.

“The 8in-diameter rear brake, of the single-sided pattern, proved to be eminently satisfactory, and neither brake was affected by rain.”

He wasn’t so impressed by the handling, however, and “at the very high speeds that the Ariel was capable of attaining and sustaining,” the road-holding came in for some criticism.

“When the model was banked at speed on an uneven road surface,” he wrote, “disagreeable yawing symptoms set in, which could not be counteracted by screwing down the steering damper.”

The source of the trouble, he thought, might have been the short-link swinging-fork rear suspension system, which on occasion, became over-lively, but he had no such qualms about the hydraulically damped front fork, which had a long, smooth action and behaved commendably.

In any case all this was finally sorted out in what was arguably the last and best ‘Squariel’ of all – the Healey 1000/4 that was introduced by Ariel Square Four enthusiasts George and Tim Healey at the 1971 Earls Court Motorcycle Show.

After acquiring a large assortment of spare parts, they improved the Square Four’s power output to a claimed 52bhp with a redesigned camshaft, better engine lubrication and other improvements, then fitted the engines into truly modern, lightweight frames with modern suspension and bitingly-powerful brakes.

With a weight of just 355lb, the Healey 1000/4 had a top speed in excess of 120mph but only 28 were ever made between 1971 and the brothers’ workshop in Bartlett Road, Redditch, finally closed in 1977, unable to compete with the new generation of Japanese Superbikes.

The Healeys that survive remain sought-after machines – but if only Ariel had been able to do the same years earlier.

Read more News and Features at www.oldbikemart.co.uk and in the latest issue of Old Bike Mart – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly paper. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly paper. Click here to subscribe.