Eyebrows were raised when Yamaha entered the ‘big single’ market in the 1970s – but it had done its homework thoroughly to put some tired old bogeys to rest, writes Steve Cooper.

Without exception, every motorcycle we’ve looked at in Old Bike Mart’s middleweight series has run a multi-cylinder engine because, in the period we tend to cover, single-cylinder machines were generally the preserve of tiddlers, with the occasional foray into 250cc territory.

Quite simply, Japan had the good sense to keep away from big singles and focus on machinery that they knew would generate reliable sales. Even if older riders from the period might have bemoaned the lack of big feisty singles, the commercial reality was something rather different.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly newspaper.

Click here to subscribe & save.

When BSA went under, the curtains closed on what had been almost a British preserve – lusty motors delivering huge gobbets of torque, capable of pulling out tree stumps, tuned one-lungers ready to battle with all and any takers on the local bypass, massively long-stroke engines capable of hauling infeasibly large sidecars stacked with kids, and engines offering almost incredulously high mpg figures.

In reality the Great British single was occasionally one of these, rarely two, and never boasting all of these fine attributes at the same time. Rose-tinted goggles have a strange way of twisting the past!

If any of the major Japanese players was ever going to produce a facsimile of Blighty’s best then it was always going to be Yamaha.

Consistently maverick in their approach to concepts and designs, the Iwata organisation had already cocked a snook at convention back in 1970 when it launched its XS-1 650 parallel twin.

Even if it never handled like a Dommie or went like a Bonnie, it sold in huge numbers.

Figures in excess of 400,000 are generally accepted as being conservatively accurate – no bad deal for a 15-year model run.

In 1975 Yamaha launched arguably its most outrageous model to date, the XT500, based around an overhead cam motor running a two-valve head, whose designers had opted early on for a slightly oversquare bore and stroke.

The concept of making a slogger held little attraction to Yamaha, and every effort was made to distance the bike and its motor from everything that had gone before it.

Never intended to be a full-on performance device, the engine tended to offer a good, honest bhp figure in the low thirties, with a healthy slice of torque.

Being an overhead cam motor, however, it was intended from the off to be revved in use. The XT delivered its maximum foot pounds and bhp at 5400 and 5800 rpm respectively – not massively high revs but certainly sustainable ones.

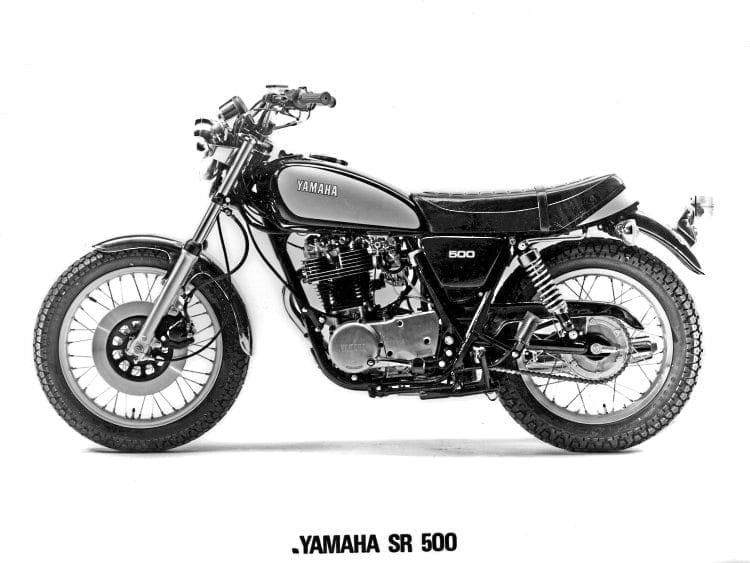

The road-orientated SR500 that arrived in 1978 had larger valves and a different piston, along with changes to the cam and crank, upping power by around 10%, although torque was largely unaffected.

If the pundits of the day had expected and hoped for BSA B50T and Velocette Venom clones, they were to be cruelly disappointed, because Yamaha had done its homework well and burned innumerable drums of midnight oil into the bargain.

These were considered new designs – Japanese takes on the concept of the big single – and huge levels of research had been undertaken to ensure that the so-called foibles of the older designs had been negated.

The arch-nemesis of many a classic pushrod single had been the almost obligatory oil leak, and Yamaha knew that there were several issues that governed this, such as pumping volumes (relatively hard to alter significantly), dimensions of mating surfaces (fairly simple to arrange during design) and, crucially, oil pressure (again, something that has to be considered at the design stage).

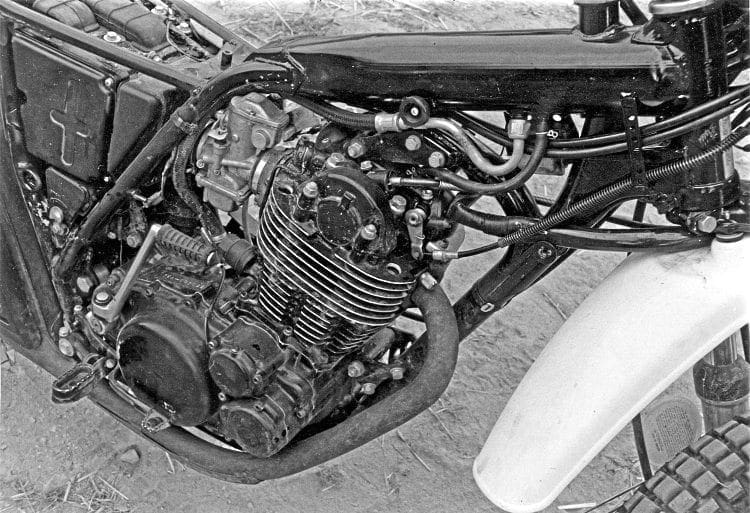

Iwata’s engineers had learned a lot, and researched even more, before even considering prototypes. Harking back to lessons already learned with the XS650, the motor was drawn up running a one-piece con rod on a pressed-up crank with needle roller big end bearings.

Such a set-up requires only a continuous supply of low-pressure oil to run well, so in a single stroke, the old bogey of oil leaks was firmly put to bed.

The rest of the engine/gearbox unit details were pretty much standard Yamaha fitment, and only the frame deviated from custom and practice.

From the off, the XT and SR ran different cranks, each one designed exclusively for its respective end role. Yamaha’s considered approach was that a one-size-fits-all mindset was never going to be acceptable, even if the two models shared a single point of origin.

With the motor designed as a dry sump as opposed to the wet sump Yamaha four-strokes before it, an oil tank was required.

Here the designers borrowed heavily from later British practices and, quite possibly a first for a Japanese firm, Yamaha opted to use XT/SR frame as the oil tank with the filler neck located just behind the headstock.

When the XT was rolled out, many struggled to comprehend why Yamaha had taken such a bold move, but within months the bike was a genuine unqualified success in America, where it mattered, on the dirt.

And almost immediately the bike was offered in stripped-down format as the TT500 for semi-professional use, yet this was soon topped when Swedish former world champion Sten Lundin built what became known as the HL500.

This proved to be remarkably successful, and was to be the last four-stroke single to win a motocross grand prix for many years.

The XT also went on to win innumerable desert races both as a factory machine and in the hands of privateers.

Over time the bike’s capacity was to grow to 600cc and would remain in a recognisable format on Yamaha’s sales sheet well into the 1990s.

The SR500 found a ready market in mainland Europe, Australia and America, yet perversely never made significant impact upon the one market that had spawned its very existence.

British riders never really grasped quite why a second generation 500cc road-going single was even necessary, and sales were always minor league, but elsewhere the bike remained a firm, if niche, favourite.

In various guises and with a variety of front brakes, the SR500 was still available as late as 1999 and beyond in some markets before it was pensioned off.

That should have been the end of a design that started out around 1972, but Yamaha had other ideas and, using the Japanese market 400cc homologue as a basis, the bike was equipped with fuel injection to make it Euro compliant and – hey presto! – the big banger for a new generation.

Large four-stroke singles are far from being the dinosaurs some might have us believe.

Read more News and Features at www.oldbikemart.co.uk and in the latest issue of Old Bike Mart – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly paper. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Old Bike Mart reading in the monthly paper. Click here to subscribe.